Table of Contents

If you are not new to Frontend development, you have heard about evolution in Flux, Redux and React, and most likely, have tried it or directly used it in a project. It comes with no surprise since the popularity of React is undeniable. React’s success is attributable to its simplicity, ease of use and a great community.

Evolution in Flux

What is also true, is that I would bet most of you used React with Redux. Both libraries go hand in hand so often, it’s difficult to imagine it’s possible to use React without Redux. Nevertheless, believe it or not, React is a library for building user interfaces developed by Facebook, and Redux is a library for managing application’s state developed by.. Dan Abramov and Andrew Clark, not Facebook. Facebook has its own library to do that job, which is Flux. Despite Flux being released about a year before Redux, and coming from Facebook itself, the de facto standard to use with React is the latter.

Moreover, I only met a handful number of developers that actually used flux’s package. Which always allowed me to nag about how much I miss the simplicity of the “pub-sub” nature of Flux, and therefore having a listener in the View for being able to react to a specific change in application’s state. Something that in my eyes, got lost with Redux.

To achieve this in new Flux, a Store, after processing an Action (event), must “manually” emit a new event, that will be listened in the view, which will allow us to trigger a callback function to react to that change. Despite adding verbosity and certain complexity to the code, it was a beautiful tradeoff to avoid the connect binding of Redux, that although working nicely most of the times, sometimes forces the developer to use componentWillReceiveProps lifecycle method to distinguish what props has actually changed, falling into if nightmare inside the method, to check what exactly changed in props.

Of course, Redux brought some great concepts, such as reducers being pure functions, immutable state (a new state is generated instead of modifying the existing one), and some, in my opinion, more about cosmetics and ‘good sounding’ statements, such as single store === single source of truth.

Recently, when coming back to Flux documentation, I was surprised to see no reference to the pub-sub implementation I mentioned before. It was just gone. Instead, all examples only referenced stores that extend ReduceStore, from ‘flux/utils’. Doing some digging, I ran into this closed issue on flux’s github repository. Basically, new Flux implemented their own version of Redux, where stores implement a reduce method that is a pure function that returns a new state of the store. Because of this, I considered it would be interesting to compare how Flux used to be implemented, and how it is being used now.

In this public repo, you have a working example of both data flows. In `AppContainer.js` you can find two React components `AppViewOld` and `AppViewNew` being rendered. To see the full implementation feel free to clone the repository and play around with it. Here, I would like to only focus on the difference that appears in the view component.

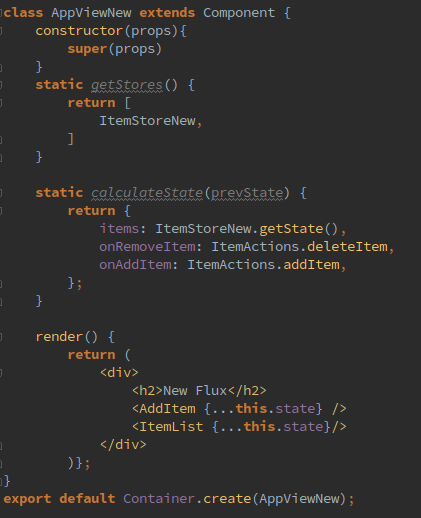

In case of the `AppViewNew.js`:

Here, we find some boilerplate with static functions getStores and calculateState, nevertheless, in the components AddItem and ItemList we will have access to the State defined here via this.props. And most importantly, whenever the store updates its state, items will get magically updated. Which in this simple example, looks like a great thing, but when the complexity of the application grows, this can bring some headaches to the developer.

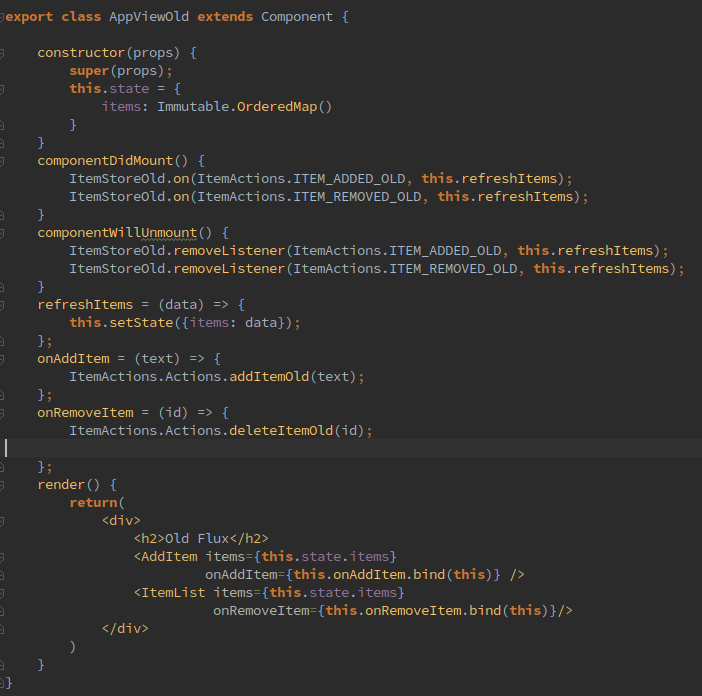

Now, in case of `AppViewOld.js`, what we will find is:

Here we see much more boilerplate, especially when we manually subscribe and unsubscribe from Actions, using React component lifecycle functions. Nevertheless, the legibility of the code is simpler. We see to what events (or actions) will this particular view react, and more importantly, what will be the effect on the view once these actions happen. In this case, it’s the function refreshItems that applies the only change to the state of the view. Moreover, we could set a different callback for ITEM_ADDED_OLD and ITEM_REMOVED_OLD actions, both of which interact with the same part of store’s state; something that we do not have with the first approach, where we only know that items have changed, but not if a new item was added, or if some item was deleted from the list instead. In fact, to actually differentiate this we would need to use componentWillReceiveProps lifecycle function, with a quite an ugly IF comparing the old state and the new one.

If you would like to get more information about evolution in Flux, I highly recommend you to subscribe to our monthly newsletter by clicking here.

And if you found this article about evolution in Flux useful, you might like…

Scala generics I: Scala type bounds

Scala generics II: covariance and contravariance

Scala generics III: Generalized type constraints

F-bound over a generic type in Scala

Microservices vs Monolithic architecture

iOS Objective-C app: sucessful case study

Mobile app development trends of the year

Banco Falabella wearable case study

Viper architecture advantages for iOS apps