Table of Contents

This is the introductory post in a two-part series, exploring the world of Serverless and Edge Runtime. The main focus of this post will be Serverless, while the second one will focus on an alternative, newer approach in the form of Edge Computing. The second part of this article will soon be available on Apiumhub’s blog.

Understanding the Serverless Paradigm

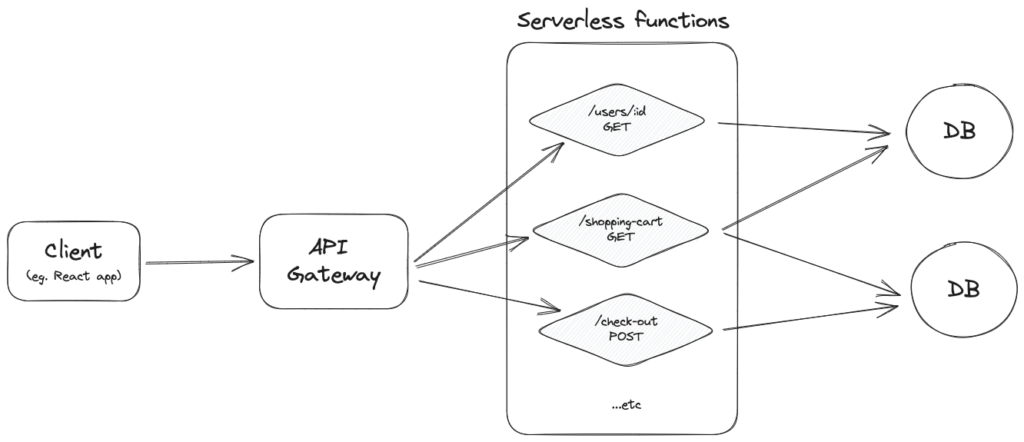

It is probably best to start by attempting to define what exactly is being discussed when the term “serverless” is used. With serverless, we as developers are no longer responsible for provisioning and maintaining the underlying servers for our applications, hence the name server-less. Coming from a more traditional background, this might seem like a crazy idea. If we aren’t responsible for managing our servers, then how would our APIs be served to our customers? Of course, it is just an arguably questionable choice of a word: there still are servers under the hood, but these are no longer created, scaled, or maintained by us, the developers. In a serverless architecture, our cloud provider spins up new instances of a server whenever a request is received.

Indeed, every request gets its own server.

These instances (usually) get deleted shortly after the request is served.

It is quite a radical shift in paradigm; it emphasizes the importance of developers addressing their business problems at hand rather than worrying about the server infrastructure. No longer do we have to think about how many servers we have, where they are, and which one takes which request. We don’t have to try to make enough servers to facilitate the requests; the requests ‘make’ servers for themselves. Then these servers scale down to absolutely nothing, so we only pay for the small amount of computing we’ve used. Even at a massive scale, this approach can often be less expensive than owning and managing our own, persistent servers.

Like with most aspects of software engineering, whether to go serverless is a sensible idea depends on your circumstances. It might be a no-brainer to go with it if you are an indie developer or startup, with a few hundred users who might occasionally call one of your APIs. You could end up with a monthly bill of cents while providing a similar experience to your users as with a more traditional VPS. Case in point calls to mind Brandon Minnick’s recent talk at NDC Oslo, in which he explains how he hosts the backends of his personal mobile applications on AWS Lambda (an extremely popular choice to host serverless functions), for less than the price of a single coffee, each month.

However, if you have been building monoliths, with countless API endpoints, this might still sound crazy – surely, if thousands of users per minute are hitting hundreds of APIs, the cost of this would be unimaginable! This is a fair concern – the post you are reading right now was written mere weeks after Amazon Prime Video came out with an impressively transparent post of their own, in which they detail how they migrated one of their solutions from a distributed, serverless architecture to a classic monolith, reducing their cost by 90%.

Let’s address this point now.

Scalability

Of course, going serverless is not only for small projects. In hindsight, Amazon Prime’s huge project didn’t benefit from going serverless with their solution, due to their unique bottlenecks related to processing every frame in every video essentially twice, but this does not mean that serverless solutions do not scale. Since we are not managing the instances of the servers, when the traffic hitting our serverless functions increases, our cloud provider will auto-scale our function to facilitate the higher load. Vice versa, when the traffic decreases, they scale it down, even to not running at all, thus not charging our account as per the pay-as-you-go model. With traditional, managed servers, this might be a bit more challenging to replicate, especially if auto-scaling is not available.

Avoiding unexpected bills from autoscale

Since our serverless solution auto-scales depending on how much traffic it gets, it is a fair question to ask what happens if an unexpectedly large amount of requests start to hit our functions, in the worst case with malicious intent, trying to DDoS our system. With the pay-as-you-go model, this could ramp up a rather large invoice at the end of the month. In early 2023, there was quite a discussion around this topic on tech Twitter, as multiple open-source products, probably most notably ping.gg, an online video-call startup was getting 1 TB of traffic going through in a 20-minute window. At the end of the day, with sensible cost-capping, budget alerting, and quota limits, having our bills skyrocket will not happen, as most cloud providers do offer these features. Rate limiters and throttling are also approaches that could be useful in avoiding situations like this. Of course, there are (and probably will always be) horror stories of unexpectedly high bills, but if the above-mentioned steps are considered, deploying a serverless system should not be any scarier than provisioning a standard server.

Resilience, security

It is worth mentioning the automatic fault tolerance that most serverless providers offer: typically, a built-in mechanism for failures or issues is present, out of the box. Since our application is distributed across multiple servers, in the event that a specific server encounters operational issues, our cloud provider migrates our application over to a healthy server. This tends to require no manual intervention from our end, increasing the reliability of our services.

Another baked-in feature tends to be out-of-the-box security best practices set for the servers. The serverless provider takes care of infrastructure security (eg. patching, monitoring, intrusion detection). Providers also commonly offer fine-grained access control and authorization mechanisms, allowing us to define a more granular permission matrix for our functions. This usually simplifies the security management on the developer’s end, thus reducing the risk of misconfigurations or introducing vulnerabilities by accident or lack of familiarity with security (which is a whole field in itself).

While these two points are quite attractive, they can imply vendor lock-in: we rely extensively on our cloud provider’s infrastructure, ways of working, APIs, deployment models, conventions, and so on. If we decide to switch vendors, it may end up being quite a painful migration, therefore it’s important to consider the potential impact on our application’s portability and the long-term viability of our chosen provider. In the amazing book, Building Evolutionary Architectures, this is noted as an anti-pattern, known as Vendor King: “an architecture built entirely around a vendor product that pathologically couples the organization to a tool”.

Cold starts

As of 2023, without a doubt, the biggest consideration to note about this architecture is the infamous cold start: whenever a request is received, a new instance of our function spins up. This obviously takes time. If we connect to a database inside our function, establishing the SSL/TLS connection could add considerable time on top of it. Referencing Brandon Minnick’s presentation again, he noted the following numbers, for ARM64 architectures in .NET:

- 50th percentile for:

- .NET 6: 873ms

- .NET 7: 372ms

- 90th percentile for:

- .NET 6: 909ms

- .NET 7: 435ms

Most cloud providers offer a ‘warm start’ solution, to mitigate this problem: after an instance of our function spins up, it hangs around for a few minutes (usually 10-15), to serve any other incoming requests afterward. This eliminates the start-up time for the follow-up requests since there is no need to provision a new instance of the server, nor to establish the SSL/TLS connection to a database since we can “reuse” the previous server. Using Brandon’s statistics, for warm starts, the numbers change as:

- 50th percentile for:

- .NET 6: 5.5ms

- .NET 7: 6.7ms

- 90th percentile for:

- .NET 6: 9.2ms

- .NET 7: 12.5ms

Stateless

We also need to keep in mind the implicit attribute of being stateless, when our servers are short-lived. We simply cannot persist state, since our servers will be dropped in minutes. This, however, is the key that enables our solution to be ephemeral and also to scale out and be resilient, without a clear point of failure. Just think about memory leaks – in my experience, this always ends up being quite a pain to deal with, as it’s difficult to locate a clear root cause. In one of my previous, non-serverless projects, we even decided to restart our persistent backend server every night, to avoid an untraceable, creeping memory leak. With serverless functions, we simply do not need to care that much about potential memory leaks, if our servers die off after serving a single request.

Of course, a state can (and should) still be persisted, where most of the time a database is a sensible choice – keeping in mind that we cannot read or write from the filesystem in a serverless function.

What can’t be done?

There are some obvious use cases where serverless is clearly not the answer:

- Any long-running process: Most cloud providers limit the total time our functions can run (to around 10 minutes).

- Websockets: Since they are also long-running and stateful, using them in a serverless environment can be tricky. Workarounds do exist, like AWS API gateway, but there are limitations, for example, a 2-hour connection duration.

- Anything that requires to be locally stateful.

- System/file system IOs.

- Transactions: across many different functions, ensuring the scope of a single transaction is delegated entirely to the caller of the function. It’s possible to do, but gets tricky.

Build and deploy a simple serverless function

Most major cloud providers like AWS, Azure, Google Cloud, and Cloudflare offer their own version of a serverless product. In my experience, using Vercel tends to be the simplest, as the company puts a lot of effort into creating an amazing developer experience. In this quick demo, we will build a simple Go serverless function and deploy it to Vercel. The function will expect a JSON payload with a pre-defined schema from an HTTP POST request’s body and convert it to a CSV file, then return it to the caller in a synchronous manner.

We’ll first need to install Vercel’s CLI (npm i -g vercel), then create a new folder, with an “api” folder in it, where we can place our .go files. If we create an index.go file, the API will serve requests for http://localhost:3000/api. With Vercel, our functions are route-based, so given the following folder structure:

/api/index.go

/api/weather/index.go

/api/weather/forecast.goWe would have three APIs:

- http://localhost:3000/api

- http://localhost:3000/api/weather

- http://localhost:3000/api/weather/forecast

Following Vercel’s template for Go, let’s first add the following to our index.go under the root /api folder:

package handler

import (

"fmt"

"net/http"

)

func Handler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

fmt.Fprintf(w, "<h1>Hello from Go!</h1>")

}To run it locally, using Vercel’s CLI, we can run it as: vercel dev

After we made sure that a ‘Hello from Go!’ string is returned from http://localhost:3000/api, we can think about deploying it. Again, using Vercel’s CLI, we can type vercel deploy to push our changes to a staging environment, then vercel --prod to a production environment. The CLI will reply back a unique URL to our project, where we can test our serverless function, deployed to the public internet.

Now that we are a bit more confident, let’s switch back to our example – given the following JSON payload that we expect our callers to provide in a POST request’s body:

{

"name": string,

"age": number,

"jobTitle": string,

"badgeNumber": number

}[]…our serverless Go function would return a CSV file, where each row is an item from the array. We need to make sure to not change the signature of the method from the example function provided by Vercel, but we can freely import multiple packages, and do our custom logic in the Handler function, as follows:

package handler

import (

"encoding/csv"

"encoding/json"

"fmt"

"net/http"

)

// this is the incoming JSON payload's schema

type EmployeeData struct {

Name string `json:"name"`

Age int `json:"age"`

JobTitle string `json:"jobTitle"`

BadgeNumber int `json:"badgeNumber"`

}

func Handler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

// we make sure only POST requests are served

if r.Method != http.MethodPost {

http.Error(w, "Only POST requests are allowed.", http.StatusMethodNotAllowed)

return

}

w.Header().Set("Content-Type", "text/csv")

w.Header().Set("Content-Disposition", "attachment; filename=data.csv")

// parse input JSON

var employees []EmployeeData

err := json.NewDecoder(r.Body).Decode(&employees)

if err != nil {

http.Error(w, "Could not parse the JSON payload.", http.StatusBadRequest)

return

}

// create CSV result

writer := csv.NewWriter(w)

writer.Write([]string{"Name", "Age", "Job Title", "Badge Number"})

for _, employee := range employees {

row := []string{employee.Name, fmt.Sprintf("%d", employee.Age), employee.JobTitle, fmt.Sprintf("%d", employee.BadgeNumber)}

err := writer.Write(row)

if err != nil {

http.Error(w, "Could not write CSV data.", http.StatusInternalServerError)

return

}

}

writer.Flush()

if err := writer.Error(); err != nil {

http.Error(w, "Could not complete writing CSV data", http.StatusInternalServerError)

return

}

}We can test it locally via vercel dev again, then vercel deploy it – my particular URL ended up being https://vercel-serverless-go-fawn.vercel.app, therefore if you decide to run the following curl, you will be able to convert employees data to a CSV – and you might even be lucky enough to experience the cold start of the small Go application from above (which tends to be ~100ms).

curl --location 'https://vercel-serverless-go-fawn.vercel.app/api' \

--header 'Content-Type: application/json' \

--data '[

{

"name": "John Doe",

"age": 45,

"jobTitle": "Software Developer",

"badgeNumber": 58195

},

{

"name": "Jane Doe",

"age": 32,

"jobTitle": "Software Developer",

"badgeNumber": 58191

}

]'References

- Ford, N., Parsons, R., Kua, P. (2017). Building Evolutionary Architectures.

- Minnick, B. (2023). Introduction to Serverless with AWS Lambda in C#, NDC London 2023.

- Theo – t3․gg (2023). That’s It, I’m Done With Serverless*.

- Theo – t3.gg (2023). Two Weeks Of DDOS Attacks – Did We Survive?

- Melkey (2023). You Don’t Know Vercel Infrastructure.

- Cloudflare (2023). What is serverless computing? | Serverless definition.

- AWS (2023). API Gateway quotas for configuring and running a WebSocket API.

- Microsoft (2022). Serverless architecture considerations.

- Vercel (2023). Serverless Functions Overview.

Author

-

Full stack developer, with 6+ years of experience, building back-, and frontends with various technologies, designing and developing scalable infrastructures on Microsoft Azure.

View all posts